Head hunting as savage as it might sound has a biblical reminiscence when David after defeating Goliath chops Goliath's head off.

The Danu clan of the Burmans might be Danites, even though the other Burman clans are not Israelites.

The Chiangs (Israelites from Tibet vicinity) are ancestors of the Chins, & of the Shans possibly.

The Kachin clan called Nun has the very name of Joshua's father. Since Nun was an Ephraimite, would the Kachins be Ephraimites? A majority of Kachins are Christians. Their war dances & songs resemble those of North American Indians & of ancient Israel.

The name Kachin might come from Kasi, one of the Pashtun clans. The Kasi Pashtuns descend from Kasi, also known as Kish. He was a Pashtun commander & descendant of King Saul, first king of Israel. Saul's father was also named Kish. Is Helon town of Helon, in Bhamo District, Kachin State, Burma [Myanmar], named after after the Zebulonite clan of Helon? If that is the case the Kachins might be Zebulonites.

The Santals

The Santal are an ancient tribe, found mostly in North Bengal (Northern part of Bangladesh). Some believe that the Kherwars came into the land of Bengal after the first clashes with the invading Aryan tribes (2500 B. C.). Many believe the Santal probably landed in Bangladesh no later than 1000 B.C.

There is a tradition in South India that the Apostle Thomas introduced Christianity to them in 52 AD.

Lars Skrefsrud and Hans Borreson began mission work with the Santal Tribe north of Calcutta in 1867.

The Santals have an interesting myth on the creation of mankind by Thakur Jiu (Supreme God).

The Santals (like so many others) have no recorded history. We cannot be absolutely certain on anything, as very little is known. But Lars used it, he accepted Thakur Jiu as Yahweh's name among the Santal.

The Naga Tribes of Manipur

The Ganges was a river which, according to ancient records there were Israelites dwelling around.

The Brahmaputra might have recieved its name from Abraham as different scholars have pointed before about the Indian Brahmin. There's a spot called Nohemi, near the sources of the river Barak.

Nohemi is another form of the Hebrew name Naomi & Barak was an Naphtalite commander, who with Deborah the prophetess, defeated the Canaanite armies led by Sisera. The story of the defeat of the Canaanites under the prophetic leadership of Deborah and the military leadership of Barak, is related in Judges 4. Lushai (the name of some local hills) means Ten Tribes in one of the local languages.

Maram, one of the regional villages, could be a deformation of Miriam, name of Moses' sister. There are some stone monoliths found in the area. Monoliths as Stonhenge are regarded as made by Israelites. A village called Bakema has the name of Celebrated Dutchman. Dutchmen & other western Europeans are regarded as Israelites by British Israelites.

Hostility to outsiders is not uncommon among tribes organised as are these in small communities which tend to become endogamous as regards other similar communities, but which are internally composed of exogamous divisions (just as in ancient Israel).

Curiously several other Germanic (Israelite) names are also found among Pashtuns which are Israelites too. Interestingly there's a Naga clan called Kabul or Kabui (depending on the version), & Kabul is the capital of Afghanistan were the Pashtun Israelites live. In the Holy Land there's a village called Kabul too.

Tradition makes the Nagas, Kukis, and Manipuris descended from a common ancestor & is widely spread. A custom is derived from a time when the rights of the youngest son were prepotent (is this derived from the story of Joseph that inspite being the youngest he inherited the best blessings?):

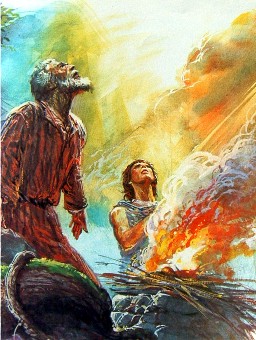

The misfortune of them having their fire extinguished was set straight by the timely intervention of the Deity, who taught them to get fire from a stone, and to this day the sacred stone from which they first struck fire is still standing and is worshipped (thanks to God the Israelites got the opposite from a rock: water).

The common feature in all these legends about their origin is the absence of any claim to be the original inhabitants of the country they now occupy (not surprising if they have ancient Israelite origin).

It's astonishing the importance the Nagas give to fire, taking it with them wherever they went as the Israelites went in the night with fire thru the wilderness. They struck the stone with a dao and thus got fire (in the same way the Israelites had to strike the rock).

The Manipuri tumbled headlong, which explains his fondness for bathing (like the Jews). The Manipuris were the Benjamin of the tribes who supported them and have gone on doing so ever since. The legend of the origin of the village of Maram presents several features of interest.

They say they came out of a cave in the earth at a place called Murringphy in the hills, about four days' journey north-east of the Munnipore valley. They attempted to leave this cave one by one, but a large tiger, who was on the watch, devoured them successively as they emerged (this story is similar to that of the Chin Israelites).

The Tangkhul Nagas, were settled in the areas they now occupy at an early date, when the Meitheis, now their masters, were yet wild and untouched by the finer arts of life.

Among the Mao Nagas we find a variant of the legend which connects the hill tribes Naga as well as Kuki with the Manipuris.

The ancestors of the village came from the west. They were a couple named Medungasi and Simoting, and it fell out that a great flood came and destroyed all mankind but these two. Finding themselves alone they did not know if they might properly marry and therefore went out into the jungle together.

What befell them showed that there was some hindrance to their union, and they dreamed that night, and in their dreams a god came to the man and told him that they might marry, but on the condition that henceforth none of their descendants should eat the flesh of the pig (the same prohibition of eating pork as the Jews with an adding of the deluge). We may notice the importance of dreams and of the divine messages revealed in them.

Now the legend current among the folk of Maram brings them from the west and in certain of the Quoireng villages it is definitely stated that at one time they lived in a spot called Nohemi, near the sources of the river Barak.

"Between Angami Naga and the Bodo languages there is a group, which I call the Naga-Bodo group, bridging over the difference between the characteristic features of the two forms of speech, and similarly between Angami Naga and the Kuki languages there is another group which I call the Naga-Kuki. . . The Naga-Bodo group . . . consists of two main languages, Mikir (Makir, having the same consonants as Mikir, was the name of a Manassehite clan. Not by chance the Chinkukis are regarded as Manassehites)... and Kachcha Naga. . . . Subordinate languages, closely akin to but not dialects, of, Kachcha Nagk, are Kabui Naga and Khoirao Naga. ...

Among the Chirus we find the legend of the three brothers who became in time the progenitors of the Kukis, Nagas, and Manipuris, coupled with the fact that in comparatively recent times they migrated, under pressure of the advance of tribes from the south, to their present homes from sites in the south-east of the valley beyond Moirang (the belief in a common origin with the Kuki Israelites makes the Nagas as Israelites likely).

The Bodo language with which they show the most important points of kinship is the eastern one — Chutiya; while Angami and Lhta are the two Naga tongues to which they are most closely allied. It must, however, be confessed that in regard to Kabui and Khoirao the classification is somewhat arbitrary, for, though they have undoubted connection with the Bodo languages, they also show many points of contact with the Kuki ones." - Sir Charles Lyall has shown good reasons for declining to accept the inclusion of Mikir in this group and finds evidence for grouping it with the Kuki-Chin languages."

The Naga-Kuki sub-group includes Sopvoma or Mao Naga, Maram, Miyangkhang, Kwoireng or Liyang, Luhupa or Luppa language, Tangkhul and Maring. The language of the Mao Nagas most nearly approaches the true Naga languages. Of these it possesses the closest resemblance to Kezhama. . . . Indeed, Sopvoma is so closely connected with all the languages of the Western sub-group (in which are included Angami, Sema, Rengma and Kezhama), that it might with equal propriety be classed as belonging to it as to the Naga-Kuki one.

The Chirus speak a language which belongs to the old Kuki sub-group of the Kuki-Chin languages, in which its fellows are Rangkhol, Bete, Hallam (in Britain there are other Hallam toponyms They are regarded by Twohousers as coming from Elon, son of Zebulon.

There are several Zebulonite toponyms like Zabulistan & others in the not distant Afghanistan), Langrong, Aimol, Kolren, Kom, Cha, Mhar, Anal, Hiroi-Lamgang and Purum (any relation with Hebrew word purim?). This last must not be confused with the Naga village of the same name, which belongs to the Maram group.

Space permits, we might enlarge our borders by extending our comparisons to the peoples of Borneo and the Celebes like the Torajas regarded as Israelites by some.

Kinship is not reckoned through females, and rights of succession (as it was in ancient Israel), both to village office and to movable or personal property, are vested in males.

Tribes such as the Chiru on the western side of the valley and the Marring on the eastern side, form connecting links with the true Naga tribes and the numerous Kuki tribes then living in the south.

On high days and holidays the men wear a much more elaborate costume than on regular days. It consists of a handsome kilt (kilts are associated to ancient Israelites like Scottsmen or Tongans) embroidered with ornaments like sequins and the headdress is the luhup with decorations of toucan feathers and tresses of hair.

The dress of Tangkhul men consists of a simple cloth worn round the waist and tied in a knot in front leaving the ends hanging down. These ends are fringed with straw pendants (like the American Indians & the Jews). The waist cloths are made of stout cotton woven in red and blue stripes two inches wide and horizontal. Over the body they wear in cold weather a long cloth in red and blue stripes to which in the case of chiefs custom permits the addition of a handsome border.

Girls wear two garments, one of which may be regarded as worn for effect only as it consists of a plain square of cloth, often dark blue with a red border, hung round the neck over the bosom. The skirt descends to the knee which it barely covers. Older women wrap themselves up in a white rug which is thrown apparently without any method over the shoulders.

The women wear small caps of blue cloth (like the Jewesses. & the color is also the favorite Jewish color) when working in the fields. Their petticoats reach from the waist to the knee and are made of cotton cloth manufactured in the weaving villages.

The ordinary dress of a Mao Naga consists of a short black cotton kilt about eighteen inches deep which is ornamented by three or four rows of white cowries, or in these degenerate days of white trouser buttons.

Red and blue are the "colors" of the Tangkhuls (like that of ancient Israel). The kilt is not assumed until the approach of puberty. Special cloths are worn by the headman and by those who have erected a stone. Many of the cloths are obtained by barter from the Angamis.

A Lushai bugler in uniform was taken for a Damai by an officer well competent to speak on Gurkhas.

The only other article of clothing worn by the men is a thick sheet of cotton cloth, and this only when the weather is cold. The women wear a piece of cotton cloth of thick texture and reaches to a little below the knee: this garment is confined round the waist by a coloured scarf with fringed ends (fringes like the Amerindians & the Jews). On holiday occasions the blue with red stripes is the favourite colour.

Over the shoulders is worn a scarf-shaped piece of cloth, generally of blue, with a border and fringe of other colours. The loin-cloths worn by the men are dark in colour, and the upper cloth is surrounded by red, blue and white lines about one inch in width, and the centre is white.

The women wear several kinds of petticoats, all of which are made at home. The general colouring is white background with red and blue stripes, while in a southern village I noticed a variety with broad khaki bands between which there were narrow red bands.

Quoireng men wear the short black kilt that is the costume of their neighbours the Angamis, with whom they have trade relations.

Very young girls have their heads shaved, but on reaching a marriageable age they allow the hair to grow long (like some Igbo Israelites).

A monarch of a country beyond Sirohi-furar ordered the miserable Nagas to tattoo their women (Where they obliged to dissobey Torah by gentiles?). I have not found any other cases of tattooing among the hill tribes in Manipur.

Among the Mao and Maram Nagas, the hair of the children of both sexes is cut close until puberty, and it is reckoned a disgrace for a girl to have short hair when she marries, or to have a child until her hair has grown to some length. The men cut the hair at the sides (is this made on purpose to dissobey the Torah that prescribed the opposite?).

To the seven families of the Murrings after their creation the deity gave pens of reed and skins of leather to write upon.

In the Mao, Maram and Mayang-Khong groups, men and women alike wear necklaces made of rows of polished hexagonal (does this shape relate with the Star of David?) cornelian beads which are valued highly. They are good judges of the quality of these beads, which they string themselves, adding, partly from economical necessities and in part in order to get more decorative effect, bones of deer carefully whitened and rounded and interspersed with blue beads.

In their festivals, the men wear their peculiar ornaments, of which the most prized are necklaces of red pebble.

Long bead and shell necklaces are worn in profusion, as amongst the Kowpoees.

The weapons of offence in common use throughout the hills are the spear, the dao and the bow and arrow. The dao is the hill knife, and used universally throughout the country.

The fighting dao is differently shaped : this is a long pointless sword, set in a wooden handle or ebony; it is very heavy, and a blow of almost incredible power can be given by one of these weapons. The weapon is identical with the parang latok of the Malays. The dao to a hill man is a possession of great price. It is literally the bread winner; with this he cuts his joom and builds his houses; without its aid the most ordinary operations of hill life could not be performed.

The arrows are occasionally poisoned with some vegetable extract. This poison, which is also used by the Kookie tribes, is a dark brown, gummy-looking extract soluble in greater part in water. The poison used by the Bhooteahs is very much the same as that used by the Marrings and Kookies.

The oblong shield which is usually carried by the Mao, Maram, Quoireng, and Kabul Nagas, is about four feet long, two feet six inches wide at the top, narrowing to two feet at the bottom.

Although never used as a weapon, the ceremonial dao of the Kabuis is of interest because it differs from the ordinary dao.

In Maram we find an interesting regulation which requires that the houses should at least not face the west because that is the direction in which the spirits of the dead go to their resting place (is this because the Holy Land of their ancestors is in the west?)

Here and there, especially among the Mao and Maram people, we see handsome drinking cups of buffalo horn (like the Vikings) in imitation of the Angami Naga.

They say that they learnt the art of weaving from a Deity who noticed and pitied their naked condition and taught them to weave cloths and to be decent.

The village blacksmith is an institution throughout this area, and he forges the spears and daos which his people require (the Israelites have been good blacksmiths & metal working specialists).

We have in this area tribes who migrate periodically and practise only the jhum system of cultivation. We have tribes such as the Kabuis who keep to their village sites with tenacity, but are compelled to change the area of their cultivation year by year in set rotation. They preserve the memory of other days by taking omens annually to decide the direction in which the cultivation is to be (any relation to Israelite agriculture?).

In crowded villages, as in the Mao group, patches of jhum cultivation exist which are semi-permanent, as they are cropped one year and left fallow for two years, which is not really long enough for any heavy jungle to grow (this jhum system, especially the resting of the fields, resembles the agricultural laws of the Old Testaments).

Among the Kabuis, Quoirengs, Marrings and Chirus, jhum cultivation provides the bulk of their sustenance.

The mountain land around the village, within certain fixed bounds, is usually the property of the village. This they cultivate with rice in elevations suited to it, and with other crops in situations unfitted for that species of grain. The spot cultivated this year is not again cultivated for the next ten years; it having been found that the space of time is required for the formation of a cultivable soil by the decay of the vegetable matter that again springs upon it.

Across the field in parallel lines, at no great distance apart, they lay the unconsumed trunks of the trees ; they serve as dams to the water which comes down the face of the hill when it rains, and prevents the soil being carried away with it.

When felling the jungle for the jhums, it is usual to leave one tree in the middle of the field as a refuge for the tree spirit. It is interesting to note the skill with which advantage is taken of the tree logs to employ them as retaining walls to keep the moisture in the ground.

Is the terraced field system evolved from the jhum system and is it legitimate to see in the details of jhum cultivation rudiments of the principles that govern the construction of the terraced

fields?

The terraced "system of cultivation gradually spread northwards from Manipur until it reached the Angamis who adopted it for the following reasons: (1) a desire for a better kind of food... (2) the impossibility of raising a sufficient crop of this better kind of food, i.e. rice, except by a system like that of irrigated terraces... (3) a good water supply. The same method of extending and enhancing the cultivable area has been employed all over the world. There are traces of terraced fields in England — and in America the system received remarkable development.

The rice grown in the hills is said to be very much coarser than the delicate varieties cultivated in the valley, and there is a tale current that the rice grown by the Kukis in their jhums is undoubtedly superior to the ordinary hill rice.

As a rule Nagas hunt in large numbers, all the men turning out to drive the game from ravines into more open country where it can be chased by the dogs and speared or shot. The Tangkhuls of the villages Hundung and Ukrul possess a special variety of dogs which resemble the "Chow".

If they kill on land belonging to another village, that village is entitled to a share of the game if any of its men be present at the kill.

The Kabuis hunt in numbers like other Nagas, and, unlike their neighbours the Kukis, also make considerable use of traps and snares. Hunting is prohibited during the cultivating season and the game have thus a close season which is extremely beneficial.

Fishing rights become valuable in the lower reaches of the hill rivers, for the upper waters are too shallow and the current too swift for much to be done there. The Quoirengs, Kabuis, and Marrings use poison, especially in the smaller streams.

The poison used is identical with that used on the arrows, and stupefies the fish so that they float on the top of the water. There are no ill efiects on those who eat the fish thus captured.

The dietary of the inhabitants is naturally restricted by the limitations on the capacity of the country to produce foodstuffs, and by the remarkable prohibitions, which from long custom possess great force, against the use as articles of food of products of the country both by whole classes of persons and by individuals either generally or under special conditions.

The staple is, of course, rice, which is cooked in earthen pots or in bamboo tubes.

Locusts are eaten (as John the Baptist did). The Naga, especially the Tangkhul, is fond of dried fish, which is imported into Manipur in large quantities from Cachar. They also eat fresh fish.

The game of draughts together with variants or derivatives, which they call the tiger and the men, and which resembles our game of fox and geese.

David playing an harp

"Hansengay". In this a circle is formed by young men and girls who move round, singing at the same time, the men heading the circle, the women bearing bamboo tubes. An instrument resembling the Jew's Harp is also used among the Mao Nagas. Other musical instruments are gongs made of bell-metal, which are purchased either in Burma or in Cachar. I have seen a fiddle imitating the "pena" used in Manipur, with a gourd covered with leather as a sounding box, hair strings and a bow fashioned from a bent bamboo with a string.

In a Chiru village near Thobal, in the valley, I saw the men playing on a goshem (does it receive its name from goshen, the area in Egypt in which the Israelites lived?),- or Kuki reeded instrument in use among the Mrungs.

Are the olive branches used by the Nagas originally taken from the Holy Land? Olive tree is original from the Mediterranean area, not from Indochina.

Naga society is patrilineal and male ascendancy is complete with them.

We have reason for holding that there were at one time ten (is this number related with that of the Lost Ten Tribes?) clans in Manipur which have been reduced to seven by the disappearance of two clans and the amalgamation of the clans Khaba and Anganba into one.

The Moirang clan is distinguished from the other Manipuri clans by its remarkable homogeneity, its special localisation in the south of the valley, and therefore in contact with Kuki rather than with Naga tribes, and its independence and by the fact that it has preserved in greater vigour than any other Manipuri clan the system of commvmal or clan genna which constitutes so important a feature of Naga life.

The institution of a communal house strictly reserved for the use of males or of females to which access is denied to members of the opposite sex, is found in so many parts of the world that it would seem to be rather symptomatic of a definite level of culture.

It is found in Australia, Africa, North and South America, Micronesia and Polynesia as well as in India, and particularly in Assam and among the congeners of the Naga and Kuki tribes in Upper Burma. Women are forbidden to enter it.

Food tabus are imposed on women (is this a kosher that became selective for women). Yet with this clear and distinct separation of the sexes there is manifested, on the occasion notably of village agricultural festivals, a recognition of the share taken by women in the communal life.

The women in some cases put aside on marriage the ornaments which as girls it was their privilege to wear or the style of ornaments worn before marriage differs from that allowed to matrons, and so far as women are concerned the style of coiffure is invariably a mark of status.

At Maram and its subject villages where pork is forbidden, so that it is usually correct to infer that a Naga who eats pork is not a Maram man.

All through this part of the hills we find a rough test in use in the rule which forbids a man to marry a woman whose speech proves her not to be of his tribe (as in the Old Testament to discover if an individual was Ephraimite or Manassehite they found it out by the accent at pronouncing shibboleth. Interestingly the Israelites' offspring in the area, the Chinkukis, come mostly from Manassah).

Is Kharasom an evolved form of Khorasan, an area which the Israelites inhabited?

The Huining people refuse to marry with girls from Kharasom on the score of the unintelligibility of their tongue. A small marriage group was mentioned to me at Phunggam, where it was alleged that, as a matter of fact, they rarely went beyond the neighbouring villages of Powi, Nunghar, Nungbi, and Huining for their wives.

Among the Mao Nagas the linguistic grouping affords no distinction between the Mao and the Maikel divisions, but they declare that they do not understand the dialects of Maram and Oinam.

The law of exogamy (only interclannic exogammy, but intertribal endogammy as in ancient Israel) prevails throughout this area in respect of the clans composing the villages.

Subject to the reservation that in actual practice the distinction of tribes rests on linguistic differences, not on any genna ordinance, the tribe is an endogamous group.

Among the Chirus is apparently necessary for the bridegroom to work for his father-in-law as well as to pay him something as a price (as Jacob did work for Rachel).

The wife cannot return to her parental home as long as there are any near male relatives of her husband remaining" (as in the story of Ruth & Boaz).

I have heard them more often express their wish to return to their native village or land, as being the grave of their ancestors, than to it being their own birthplace (Israelites felt so attached to the Holy Land that wanted to be buried there even if they were not living there as in the case of Joseph's corpse taken from Egypt to be buried in Eretz Israel.

In the case of a woman dying in childbirth the grave is dug by her male relations or else by her husband's relations inside the house.

In the Mao, Maram and Kabul groups polygamy is very rare and is not encouraged by public opinion. I have heard of instances among the Quoirengs where the two wives lived in the same house and got on well together.

There is apparently no restriction upon the remarriage of widowers, except that they are liable to the same exogamic necessity as when they first married.

They sometimes marry their deceased husband's younger brother (levirate marriage as in old Israel). Much the same rule is in force among the Mao and Maram groups, in the latter of which we find an instructive regulation to the effect that a widow may remain in her husband's house and be entitled to maintenance. If she separates, she is at liberty to please herself and to keep herself.

At Yang we begin to come upon compulsory marriage with the deceased husband's brothers, for they there preserve the tradition that in early times this regulation was in force among them (as in ancient Israel). They claim to be descended from Kukis. This custom is found among some Quoireng villages. This obligation is in force among the Kabuis.

Among the Marrings it is permissive, not compulsory. This done among many of the tribes which have been subject to Kuki influence, or which are of Kuki stock. If in cases where such marriages are compulsory, the younger brother refuses to marry the widow, he has to pay a fine. If the woman refuses to marry her husband's brother, her price is refunded, and she is returned to her people.

In some groups humanity permits children born to an ostensibly unmarried girl a chance of life dependent on the acknowledgment by the man of his paternity. In other groups, as at Mao, such children are abandoned without further discussion. A feature of the birth ceremonies among the Tangkhuls is that the first food taken by the newly born infant is some rice, which the father first chews, an act which seems to constitute an acknowledgment of his paternity and duty towards it.

The Mao people punish the girls, who used in one village to be put to death, while the Marrings punish the man.

Should the widow not be willing to be taken by her deceased husband's brother, and her parents agree with her, her price doubled must be returned to the brother." It is interesting to observe that the price doubled has to be paid in cases of adultery when the adulterer escapes the vengeance of the

husband."

Divorce is of rare occurrence, and among the Tangkhuls is given only on the fault of either party. At Mao and Jessami, in the Mao group, women occasionally divorced themselves and that in such cases the children, if and when weaned, went to the custody of the father.

Adultery is a cause of divorce among the Kabuis, who also allow divorces on such grounds as proved incompatibility of temper, or serious ill-treatment of the woman by the husband, or on her demand. In these cases, if the man is in fault or demands the divorce, the price is not returned, while it is repaid to the husband when the woman is in fault or demands the divorce.

In the event of either married party wishing a divorce, the rule is that, should the consent be mutual, there is no difficulty to separate. If the wish for a separation comes from the woman, and the husband is agreeable, her price is to be returned; but if the man wishes to send away his wife, which he may do with or without her consent, then he is not entitled to it.

Among the Marrings divorce is given only on proof of some fault, and "even then a heavy fine is levied in the shape of feasting and drinking". The Chirus do not seem to allow divorce.

The rules relating to the return of the price are also in force among the Quoirengs, who admit barrenness as a ground for divorce, and in other cases give the children to the father.!

In cases where permanent villages subsist by means of jhums, the rights of ownership are recognised in the jhums which are cultivated in a strict rotation.

Among there's a common practice of placing in the grave a number of articles which are destined or believed to be destined to be of advantage to the deceased hereafter, or which have been specially associated with and appropriated to the deceased during his lifetime (this was a practice common in Egypt & Israelites accepted many Egyptian practices, even if the practices were pagan).

The office of khullakpa or gennabura or head man is essentially representative and magico-religious. It is therefore invested with special tabus can only be held by an adult male in full health both of mind and of body.

From it are excluded persons who are mentally below the average and all who are blemished by any physical deformity. As with ordinary succession to office generally accrues on the death of the occupant; but among the Tangkhuls, the custom above described is held to apply to village office, and in other groups succession is common when the khullakpa becomes old and worn out, so that the Tangkhul custom, if not due to the desire to secure for the office a man in the plenitude of his power, physical and mental, and to secure immediate continuity in the occupation of the office.

The private householder is as regards the house-spirits a priest in his house and liable to tabus which are similar in nature, effect, and presumably in intent to those protecting and insulating the khullakpa. On the custom of primogeniture we find at Puruni, the old Kuki village, a custom by which the occupants of village offices move up in regular succession. This custom provides a succession of experienced persons and has been stated to be the custom regulating the succession to the throne of Manipur.

Among the Kabuis and Quoirengs the office of khullakpa seems to have lost much of its authority in religious matters. Elders perform many of the religious duties of the khullakpa, but the office exists and is still hereditary. The Kabuis especially have been exposed to Manipuri influence, and have come into close contact with Kukis among whom the hieratic functions of the chief are almost entirely atrophied.

While primogeniture is the most widely accepted rule of succession. Among the Tangkhuls in cases where the father dies before the marriage of a son, the general rule in many villages is that the eldest son gets a double share of the immovable property while the other sons get a single share each. The movables are then divided in equal shares, but this is by no means universal. In some villages, again, the estate of the eldest is distinctly burdened with the duty of maintaining his younger brothers.

Women do not succeed to immovable property. In default of sons, the immovable property goes to the brothers of the deceased, and the movable property is distributed among the women.

At Maikel the eldest son gets the house and the others divide the fields.

Murder within the clan is rare. The murder of a member of another clan or village would occasion a feud which would only be ended with the slaughter of a member of the murderer's clan or village, and it is known that some of the worst village feuds have originated in this manner. Accidental homicide is punished among the Tangkhuls by fine, amounting to six cows. At Jessami in the Mao group the offender has to make a short sojourn away from his house, but not necessarily outside the village; while at Liyai he is banished from the village (is this an evolved tradition to the running away to the cities of refuge of ancient Israel?).

At Mao his punishment is seven years' banishment from the village and a fine of five cows. At Maikel banishment for one year and a fine of five cows, while murder ensuing in the heat of passion in a quarrel is punished with seven years' banishment and a fine of ten cows. The Mayang Khong people exact only a fine of one cow in cases of accidental homicide. At Maram the punishment consists of banishment for one year and a fine of six cows.

Among the Kabuis a heavy fine is levied from the culprit. Both the Chirus and the Marrings impose a heavy fine in such cases. Minor assaults are punished when circumstances permit by the use of the simple law of revenge (similar to an eye for an eye).

Adultery was commonly punished so far as the male offender was concerned with death. Five cows are in some instances required for the husband and one for the village.

At Jessami the woman surrendered all she owned to her husband, who also received a fine from the lover. At Laiyi, also a village of the Mao Group, the fine is only one cow, while at Liyai, close by, the adulterer is driven out and his property seized by the injured husband, a similar punishment being

inflicted on the man at Mao, where the woman was also liable to have her nose clipped or slit with a spear. At Maikel also the woman is punished as well as the man, who loses all his property.

The Quoirengs drive the adulterer from the village, but the customs of the Kabuis in this regard have apparently undergone some amelioration since the days of Colonel McCulloch "The adulterer if he did not fly the village, would be killed; aware of the penalty attached to his offence he dare not stay and is glad to leave his house to be destroyed by the injured husband. The family of the adulteress is obliged to refund the price in the first instance paid to them by her husband, and also to pay her debts. Why these expenses are not made to fall upon the adulterer, they cannot explain".

Information collected in two large villages, as Kabui villages now go, is that only a fine is imposed, and that not by any means a large one, but that, as is the case in every village, the woman is divorced from her husband, to whom her price is returned by her family. The Chirus mete out the same lenient treatment in cases of adultery, while the Marrings inflict a heavy fine.

To turn to offences against property we find among the Tangkhuls that theft was once punished with death if the offender Avere was caught flagrante delicto. Nowadays a fine is inflicted. At Jessami (Mao Group) twelve potes of dhan must be paid by the thief as well as the restoration of the property taken.

At Maram we find the same nice discrimination, as theft from a house is punished with a fine of ten rupees while the theft of paddy from a field involves the culprit in a fine of ten potes of dhan. If the things stolen are found they are taken back, if not, it might be dangerous to accuse a man of theft.

In civil debt, interest runs after the expiry of one year, when the debt is reckoned as double. Theft, if the thief should happen to be a married man, is punished severely, but a young unmarried man might with impunity steal grain not yet housed, whilst theft from a granary. A married man therefore must be regarded as having a different status from that of the bachelor (as in ancient Israel)

The mere sight of the destruction by fire of a neighbouring village is enough to cause a village genna.

We find among the people of Mao that in cases in which rights to land or its produce are in dispute the oath on the earth is usual.

The weight of an oath is augmented by increasing its range so as to include all the members of the village in the imprecation, while it is forbidden to near relations to swear in any case between them

(Mao Group).

The weightiest oath is that which concludes with the imprecation, "If I lie, may I and my family (or clansmen or co-villagers) descend into the earth and be seen no more". At Naimu I noticed a heap of peculiarly shaped stones inside the village upon which the Tangkhuls took an oath of great weight.

Others swear by the Deity Kamyou, while oaths on a dao or tiger's teeth are common.

Karnyou is associated at Powi with a stone in a sacred grove (like those of the Israelites), and at Phimggam near Powi, Kamyou was the eldest of the three sons of a nameless Deity. To Kamyou men address prayers and sacrifice.

At Jessami the penalty attaching to perjury when the oath on the spear is used is a violent death (perjury was an awful sin in ancient Israel too). The oath, ordeal, or arbitrament of the cat, which is used both in the Mao Group and by Maram, is thus effected.

A representative of each of the litigant parties holds an end of a cane basket inside which a cat, alive, is placed, and at a signal a third man hacks the cat in two and both sides then cut it up with their daos, taking care to stain the weapon with blood.

The ceremony was a form of peacemaking or treaty, and that therefore the slaughter of the cat bound them in a kind of covenant. There is also an oath upon a creeper which is believed to die when cut, and the man taking the oath cuts the creeper saying, "May I die as this creeper dies if I lie".

In another Kabui village they offered to swear by Kajing Karei, which I pointed out to them was not one of their oaths. They agreed, and explained that it was a Manipuri oath, which is a mistake, for it comes from the Tangkhuls.

The oath consisted of taking some salt, some ashes, and some paddy husks, with the following imprecation: May we find our salt become as these ashes (mixing at the same time a pinch of ashes with the salt), may all our rice turn to husk, and may we ourselves perish like the husks, the spoilt salt, things that are only fit to be thrown to the winds, if we lie" (Jesus Christ also compairs Christians wit the salt).

The Chirus swear by the sun and on the dao, tiger's tooth, and spear. In each village there is a circle of stones, inside of which are a few stones upon Avhich an oath may also be taken.

Head-hunting is associated with the blood feud, where the duty of vengeance remains unsated until the tally of heads is numerically equal (an eye for an eye).

In Tangkhul villages are heaps of stones, — places of great sanctity, — An oath taken on these stones is regarded as most binding.

In life the Kuki chief is conspicuously the secular head of his village.

Abraham's sacrifice

The Quoireng Nagas used to take heads because the possession of a head brought wealth and prosperity to the village.

The Kukis still consult the bones of their dead chiefs and the skulls and horns of the trophies of the chase form not the least important of the decorations of the graves of the dead. Earlier authorities declare that no young man could find a wife for himself until he had taken a head and thereby won the right of the warrior's kilt, or of the necklace of bears' tusks and the wristlets of cowries success on a head-hunting raid would fairly serve as a mark of manhood and as qualifying for promotion from one stage in tribal life to the higher stage of married man.

I do not think it possible to reduce head-hunting to a single formula. I have found it connected with simple blood feud, with agrarian rites, and with funerary rites, and eschatological belief. Again it may be in some cases no more than a social duty.

The Kuki-Chin languages' influence has been considerable in this area.

It is safe to extend to the Nagas what I have in another place found to be true of the Kukis, whoso language I knew, that this feature of their material life is reflected in their language, for they have a separate name for articles and actions which we classify together. They insist on the points of difference, while we classify by identities.

Strange-shaped stones were often pointed out as "lai-pham", places where a Lai or Deity was wont to dwell (is Lai a deformed name for eLOhIm?).

Meithei and Naga alike declared that my galvanic battery was a "lai-upn" a divine box.- The Thados have borrowed from the Meithei the word laili (or in Meithei, lairik = lai + rik = likh = to write) as if they thought a written document possessed a divine potency (the scriptures are divinely revealed & have a divine potency too).

Nagas like Jews are very attached to their deceased.

There were two deities, Uri (Uri is a Jewish name) and Ura, who had four arms and four legs each. No one had ever seen a Lai (as none had seen God except Moses). (Perhaps Ura & Uri are related to Ur, Abraham's original land).

A common feature of the beliefs held by these tribes is that the creation of the world is ascribed to the deity who causes earthquakes. Among the Tangkhuls and Mao Nagas it is believed that the world was once a waste of water with neither hills, nor trees, and that the deity imprisoned below made such huge efforts to escape that hills emerged.

Some of the Mao Naga villagers add the belief that the sky is the male principle and the earth the female. The Kowpoee believes in one Supreme Deity, whose nature is benevolent. This deity is the creator of all things. Man, they say, was created by another god, named Dumpa-poee, by the orders of the Supreme Deity, but they can give no account of the nature of the creation.

The belief in a divine Demiurge who, in creating the world and sending forth the race of mankind to dwell thereon, acts not of his own volition, but by the command of a Supreme Deity, is found elsewhere in this area.

At Mao they believe in a future state. Man has power of the same order as that of deities, but less in degree. Yet there are forces which are so far greater than the power of man, unaccountable forces, operating, as it would appear, not with any regularity, but suddenly, unexpectedly, forces of destruction.

The successful rain-maker is deified (any relation with the Amerindian rain dance?). Earthquakes in these latter days are forces of immense destructivity. The thunder and lightning, accompaniments of the bursting rain reveal them as due to personages who are, if not men deified, deities anthropomorphised.

In their belief, dreams and omens afford an unerring presage of the future (as in the Old Testament we saw in Joseph's dreams & other occasions).

They attach to the dream precisely the same significance as to the actual event. Does this mean that their dreams are as substantial and possess the same measure of reality as the facts of their waking vision? If this conclusion were legitimate on these facts, the dream life would have a continuity with the waking life, and possess a specific "reality" for them.

To be attacked in a dream by a cow or buffalo is universally held to be a sign of bad luck and sickness. To be bitten by a snake is an omen of very evil portent. To wash the person is indicative of very good luck and prosperity. To build a house is a token of death, for, as the Kukis say, it means that they must set about building a house in heaven, but at Liyang, Lengpra, and Aqui it prophesies good luck in hunting.

To see a crow means trouble and scarcity, except at Liyang, where it means good health. To see a pig

means bad luck (Pigs have often bad connotation like for the Jews. Pharaoh's butler had a dream about a crow that meant his death).

To dream of an earthquake means death, poverty, or scarcity in all cases. To dream of winning a race means success in life. To dream that a dog bites one is very unfortunate and forbodes sickness, for, as the Aqui people told me, it is a dream of a witch (as in olden Israel they disliked witches).

Among the lucky dreams none is more welcomed than that of climbing a tree.

To climb a hill is fortunate, while to go down hill is a warning of death. To see a buffalo is universally a sign of bad luck.

Animals which are used in certain sacrifices, as those for sickness, are unlucky. Success in the dream portends success in waking life.

In the Meitheis a case is mentioned where so-called legislation was effected as the result of a dream, and in the story of the prohibition of pork to the people of Maram the ordinance was revealed to the ancestor of the village in a dream (was this ancestor reminding them of the food prohibitions of the Torah?).

Throughout this area we find that at all the crises of domestic and communal life omens are taken in order to determine the issue of the future. Egg-breaking, as among the Cossiah tribes, is also practised.

The Kabuis erect a pole with a bundle of grass at the top in front of the house of the fortunate man who has had the best crop in the year, and the Kukis also put grass and boughs in front of any house in which rice is stored. In all these cases the evil spirits are frightened off by the grass and herbs. A similar purpose is served by the cage which is so often seen outside a Naga house.

Mysterious sicknesses, the sudden appearance of boils, blindness, loss of speech, premature greyness, are regarded as certainly as probable consequences of breaches of the genna prohibitions. Since their attachment to the genna rules is morality of a kind, this belief contains the rudiments of the idea that physical suffering and sickness are due to sin — to breaches of what is "tribal law".

Among the Kabuis the maibas declare the lai who is causing the sickness, and thus decide upon an appropriate sacrifice. To medicine they do not look for a cure of disease, but to sacrifices offered as directed by their priests.

At Mao and in some Quoireng villages the khullakpa lets a cock go free outside the village, presumably a sort of scapegoat. We find among the Kabuis beliefs associating the python with sickness. They kill it and worship it when dead. After killing it they are genna for three days. All men capable of field work are collected at the village gate, and then shout " We are all here". The Kukis also hold that merely to see a python is a source of misfortune (as when the Israelites encountered the fiery serpents).

Colonel Shakespear holds the view that the Lairen (Meithei) is identical with the Rulpui of Lushei belief, which is undoubtedly not a python, but a mythical form of snake (like the mythical snake of the Bible called Leviathan).

I think that the erection of stones has a closer connection with the rudiments of ancestor worship than is often suspected (like at Stonehenge).

Among the Tangkhuls and other tribes we have the legend of the angry deity who brandishes his dao and stamps in anger on the ground, thus causing the lightning and the thunder (like Thor with his hammer).

Among the Tangkhuls we find that the deity Kamyou, the eldest son of the Creator of all things, is worshipped by man. He is armed with a big stick, and does judgment upon evil doers, and appeals are made to him because sickness is held to be the result of evil acts.

The "celebrant" acts in a representative capacity. Certain animal is definitely forbidden when a sacrifice is made to a great snake as the deity to whom sickness is attributable (the wicked Israelites started snake worship). In the case of domestic sacrifices the sacrifice takes place inside the house, and is consumed there. In cases where a sacrifice is made on behalf of anyone in sickness, the animal sacrificed is not given to him to eat.

The sacrifice of a buffalo or cow seems to be incidental to a rite of worship of a deity (as the Hindus, the Israelites started cow worship or calf worship in the wilderness). Fowls are offered as sacrifices to the House spirit, and to the sun and moon (Israelites also worshipped the sun & in sum became polytheists). In the case of the village genna as practised at Mao, the cock is not killed, but let go, probably as a scapegoat rather than as a sacrifice.

Both Colonel McCalloch and Dr. Brown identify the village priest with the maiba, who is doctor and magician in one. Inquiries show that the khullakpa is the village priest, and that the head of the household is the priest in all purely domestic worship. In many respects it is easy to distinguish the maiba from the khullakpa. The maiba is generally not an hereditary officer, while, the succession to the khullakpaship is hereditary.

The maiba cannot order a village genna. He interprets dreams and omens. The khullakpa, however, plays the leading part on all occasions when a village genna is held. He acts whenever a rite is performed which requires the whole force of the community behind it.

The maiba owes his position to his own individual talents. There is a fundamental difference between the maiba and the village priest.

The Kabuis bury the navel cord under the stone hearth inside the house. In some cases an old woman of the village helps the birth but in other villages the father acts as midwife. In any case all in the house are genua, secluded from the rest of the village.

Five days after the birth of a child it is named with various ceremonies: names are not given at random but are compounds of the father's and grandfather's names, or those of other near relations" (as in the birth of John the Baptist we can see that Jews then didn't usually name their children unless a relative had the name too). Omens are taken in order to select the most favourable compound, for the name exerts a profound influence over the life of the individual (Jews also believe in the influence of the name on the individual). In the Old Kuki village, Sadu Koireng, in the southern portion of the Manipur Valley, this method of nomenclature is practised. The child receives the name of his maternal grandfather. Differences of coiffure mark the different stages of social maturity.

The religious aspect of the ceremonies of marriage is enhanced by the custom of taking omens as to the day on which the marriage should take place, for marriage is the severance of the woman from her clan and the consequent accession to the man's clan and household of a member by birth of another clan (in tribal Israel the woman also belonged to her husband's tribe as seen in the diminished Benjamites' story).

Songs are sung, but among the Tangkhuls it is expressly forbidden to sing war-songs. The employment of a go-between is common, and if it is due to the avoidance which is necessary between engaged persons, it may be connected with the genna which prohibits intercourse between the newly married couple for the first few days of their wedded life. This prohibition does not operate in the case of the re-marriage of widows, a fact which suggests that the genna is in part due to the fear so often observed of entering into strange relationships for the first time.

All these tribes bury their dead. Tree-burial is a common practice in the suroundings & it was practiced by the Israelites. Of the Kabuis Colonel McCulloch remarked that "The village and its immediate precincts form their graveyard and when for a time, from whatever cause, they have been obliged to desert their village, I have heard them more often express their wish to return to it as being the grave of their ancestors than as being their own birthplace" (in the same way Joseph & the other Israelite patriarchs were buried in their land).

But not all the dead are buried inside the village or in the usual burying place. In the first place the children of tender years who die before they are weaned are often not buried in the ordinary grave but close to the house. In the second place, those that die outside the village must as a general rule be buried outside the village, though there is either a ceremonial burial in the usual place or the burial of some part of the remains or belongings of the deceased.

At Uilong a man killed in war is buried outside the village on the side of the village opposite to that on which live the enemies who inflict the fatal wound. Among the Quoirengs and Kabuis a woman who dies in childbirth is buried inside the house. The Quoirengs in such cases bury all the moveable articles and utensils in the house, while the Kabuis abandon the house and its contents completely.

On opening this family grave the bones are collected, cleaned with water, and then wrapped in a large cloth, new or old, and put on one side of the grave (as in in Madagascar do). Burial takes place, as a rule, on the day following death except in the cases where children die or where death occurs before sunrise (the Jews also bury people quickly).

In the graves are placed various articles for the use and comfort of the deceased in the world hereafter (an Egyptian costum taken by pagan Jews?). The Tangkhuls bury two old cloths with a man for his own use and a new cloth as a present for the Deity of Heaven.

All the relations now gather round and make great lamentation (like the arabs). Around a fire the family sit and wait for any sign in the fire-place, such as the print of a foot, to see if there are any more deaths to be expected.

After the harvest in December has been gathered in, and all instruments in connection with the same have been put on one side, in the evening the rich kill a cow, the rest pigs and dogs, and for those whose children have died, eggs are boiled.

All friends who come forward to help in erecting the ' wonyai thing ' are counted, and to them a liberal supply of meat and beer is distributed. They then go off and bring in the wood and rope necessary to erect this structure. It is a lightly made structure, built outside the door of each deceased's house, and is shaped like a shield with a sort of small platform in front, on which the following day are placed various articles, such as Indian corn, roots, pumpkins, etc.

The "Kathi Kashdm" Feast takes place about the end of January of each year. The first thing for each family to do is to procure their buffaloes, cows, pigs, and dogs. After they have procured these from near and far, the headmen of the village give orders for the beer, weak and strong, to be prepared for fermentation, and they also, after a palaver, decide what day the feast shall commence. It is a ten-day feast.

Both males and females join together in getting in a plentiful supply of wood ; and as there is much entertaining during this feast, and all night singing and dancing performed, there is need of plenty of fires, it being the coldest part of the year. The representative of the dead finds his first occupation on this day by collecting "khamuina", a kind of broad plantain leaf used for the unleavened bread (the Jews also use unlevened bread for certain festivities) made the next day.

Unleavened bread is made into small cakes, cut up into small pieces, cooked and offered to "kameo" and then distributed with a small cake of bread wrapped in the "khamuina" leaves amongst the mourners in each section of the village. On this day also cloths of all kinds and qualities are attached to long poles and erected outside each house of the dead. The more cloths displayed the greater one is thought of .

The Seventh day is the day when the real excitement commences (because it was the Sabbath?). Friends and relations from villages around come in during the afternoon, and at sunset. Before their arrival the females only give an offering to "kameo" in the shape of a sandwich of unleavened bread (they eat unleavened bread like the Jews on the 7th day).

The spirits after entering the torches are declared to wend their way during the evening towards the hills on the north, and finally disappear to find themselves crossing the river.

At death something leaves the body. That something is often regarded as a winged insect of some kind, now a butterfly, now a bee.

The "ghost" of the deceased is regarded as an exact image of the deceased as he was at the moment of death, with scars, tattoo marks, mutilations, and all — and as able to enjoy and to need food and other sustenance.

The Tangkhuls say that their dead go to a heaven by a path over the crest of Sirohifurar. This is the realm of the Deity. The king of Kazairam, what we might call the place of departed spirits, is named Kokto. He is supposed to live in a grand mansion, with sentries guarding all sides.

Kokto judges them all, and, after appropriating for himself all the best cloths brought along, he sentences the thieves to go by the road to the left where there are worms and everything dreadful, and the honest spirit turns off to the right, and follows a road which can only be described as clean.

At Jessami I was told that the good go to a Heaven above but the bad are consigned to an abode beneath the earth. There is also said to be a nice place inside the earth to which the dead go, but I do not know whether it was A place of lasting abode or a temporary sojourn. At Maram the Heaven lies in the west (like their loved Holy Land?) and it too is divided into many compartments. Of the Kabuis we have the statement that "After death the souls descend to an underground world where they are met by their ancestors, who introduce them into their new habitation; the life they lead in this underground world is an exact counterpart of what they have led in this.

Heaven is in fact regarded down to the minutest details as an exact replica of this "material" world. Maram is said to have had its origin from immigrants from the west and their Heaven is in the west (Israel?).

Sin consists primarily of breaches of the unwritten laws of society. What gives validity to these unwritten laws is the fear that something may happen if they are broken. This terrible death of a tribesman, has happened. Why did it happen? What more logical than the answer that it happened because a sin has been committed? (in the same way in the New testament Jesus heals people & the ones around wonder who sinned, the parents or the individual of the person that He healed?).

The term "genua" means simply forbidden or prohibited. It is therefore applied in its primary sense to the mass of prohibitions, permanent and temporary, periodic and occasional, which form so important a part of the tribal law of these societies. All the rites and festivals observed by social units in this area are characterised by a prohibition of the normal relations with other social units.

"The word genna may mean practically a holiday — i.e. a man will say, ' My village is doing genna today,' by which he means that, owing either to the occurrence of a village festival or some such unusual occurrence…his people are observing a holiday; genna means anything forbidden".

Namoongba is a periodical closing of individual villages. This custom does not take place with any regularity, and its object is some kind of worship. One of the occasions is just before the jungle which has been cut down on their jhooms is fired: this lasts two days, and the villagers are said to fast during that period: the village remains shut up during the two days, and no one is allowed either entry or exit, and it is also affirmed that anyone attempting to force an entrance during this period would be liable to be killed.

On other occasions the proceedings are of a joyous nature and may take place after a successful hunt, a warlike expedition, a successful harvest, or other striking event: on these occasions feasting and drinking is the order of the day. "Gennas sometimes affect whole villages, sometimes only chiefs or single households".

The penalty attaching to a breach of either of these regulations falls rather on the actual offender, though it might be fairly described as a social sanction because there is always the fear of some calamity happening in their midst as the result of disregard of any one of these ordinances.

The village is an economic unit, so that all the ritual observed for the cultivation of the staple, rice, necessitates the expenditure of communal energy in the form of village gennas.

There are village gennas connected with the first fruits.

At all these village gennas the ordinary routine of life is profoundly modified if not broken off altogether. There are special gennas imposed on these occasions which require abstinence from certain kinds of food.

The ill effects of an interruption of a village genna are sometimes irremediable, while in other cases a repetition of the genna is adequate to prevent all harmful consequences. At all the village gennas the gates are shut when the genna begins so that the stranger that is within the gates may not go forth and the friend that is without must stay outside (this resembles the day of the death of the first begotten of the Egyptians when the Israelites stayed at home waiting for the destroying angel).

Among all these tribes from the day of the first crop genna to the final harvest home all other forms of industry and activity are forbidden.

All hunting, fishing, tree and grass-cutting, all weaving, pot making, salt working, games of all kinds, bugling, dancing, all trades are strictly forbidden — are "genna".

The Kachin and Chingpaw customs are very similar to those of the Nagas. At Mao I learnt that they worshipped the Sun as a good deity and sacrificed a white cock to him.

At Maram we have six gennas for the crops and one for the game. The two additional crop gennas are held one when the rice begins to show through the ground, before transplantation, and the second in connection with the growth of the ginger root. Their form of rain ceremony is to descend to the river, the Barak, and there to fill vessels (bamboo chungas) with water, which they empty over their fields and pray for rain.

The Reengnai, in or about January lasts for three days.

The last genna of all is named Pumthummai, which lasts for one day, and celebrates the end of the harvest. The cultivation omens are taken by two elders who wash their bodies very carefully and put on new clothes that day. The rotation of cultivation is fixed and known beforehand.

The Chirus have six crop festivals, one of which, that before the crops are cut, is marked by a rope-pulling ceremony of the same nature as that observed among the Tangkhuls. In order to get rain, they catch a crab in a neighbouring river, put it in a pot with water, having fastened a thread to one of its claws, and then keep on lifting it out and letting it fall back into the pot.

At Jessami one of the regular village gennas has for its purpose the prevention of sickness throughout the year. A party of young men is sent out to catch a bird, and if they are so fortunate as to bring back to the village a fine big bird such as a toucan (or hornbill), it is an unerring omen that there will be no sickness in the coming year.

This genua lasts for eight days. The Kabuis observe a genna in January in order to protect themselves specially from hurt by bamboos. It lasts for one day, and on it the young men are forbidden to drink outside their houses.

The clan is important, sociologically, as the marriage unit for marriage of members of the same clan is strictly forbidden. Were this rule to be broken, some dreadful calamity beyond description would happen to the village.

Household gennas are occasioned by events such as the birth of children.

Among the Tangkhuls the husband may not go out of the village or do any work after the birth of a child for six days if the child be a boy or for five days when the child is a girl. So also strangers are forbidden to enter his house during this period lest harm should come to the child. If a woman comes in to act as midwife, she too is genna. At Sandang one of the cloth-weaving villages the period of restriction lasts for one day only and we have the interesting information that the father may not touch any one for fear of harm coming to the newly born infant.

The head of the household is the person who performs the rites incidental to the worship of the house spirit and the sacrifice of a fowl which is part of the genua is made by him. Now the birth genua includes the ceremony of naming the child which takes place on the last day of the birth genua and for the purposes of which the sacrifice of a fowl is necessary as the name is determined by omens.

In the Mao group both parents are genua and at Jessami this lasts five days, while at Laiyi Liyai and Maikel it lasts for fifteen days at least in the case of all except the eldest child, when it is, or was, prolonged to thirty days. At Mao the genna for the first child is ten days and for the others five days.

A cock is sacrificed for a boy and a hen for a girl, but whether the taking of omens is the main or a secondary purpose is not clear.

At Maram they say that at one time this genna lasted for one month but is now observed for ten days only, during which neither parent may touch any other person nor may the woman eat any food except fish and salt. A fowl is sacrificed on the day of birth.

At Liyang a village which I know is not a pure Quoireng village, the birth genna lasts for one month, during which the only food permitted to the parents is fish and fowl, meat of any other kind being most strictly forbidden.

At Lemta and Maolong the fowl which is killed on the birth of a child may not be eaten by the father, who, at Taron, is kept without any food that day. The flesh of fowls is not regarded as meat. The Kabuis appear to have a birth genna for the first child and do not allow the father to eat, drink, or smoke that day. The Koms prolong the genna to one month for the birth of a son and for the birth of a daughter regard five days as sufficient for the father, who may do no work during the genna, and may not go far from the village, while exacting a month from the mother. The Chirus are genna for one month.

"There are many prohibitions in regard to the food. KhuUakpas are entitled, perhaps required, to wear special cloths, the use of which is forbidden to all others except those who erect a stone monument. Before setting forth to select a stone, the household of the " lung-chingba " are not allowed any food except zu and ginger. Marital intercourse is strictly prohibited the night immediately preceding the day on which they choose the stone.

On the day the stone is brought inside the village, the villagers may not use their drinking cups, but have to drink from leaves.

On the occasion of the first crop genna, pigs are forbidden. In the Maram group we have the general prohibition of pork.

Young unmarried girls are not allowed to eat the flesh of male goats, and in one village which is not far from the influence of Maram, women are not allowed to eat pork.

The first fruits are "genua" until rendered available for general use, by the action of the khullakpa. There are thus gennas affecting the various social units, the tribe, the village the clan, and the household. There are gennas based on the classification of society by age and sex and social duties.

Stone monuments consist of (1) monoliths are found either singly or arranged symmetrically in rows, avenues, circles or ovals; (2) cairns or heaps of stones; (3) single smaller stones; and (4) the flat stones near Maram, supported on smaller stones.

Monoliths abound in this area, but the simmetrical arrangements of monoliths are found. at Maram and the village Uilong and in the Marring area. Outside the once large and prosperous village of Maram there is an avenue of stones, nearly all of which are still standing, and inside the village one can see the remains of, or parts of, a circle of stones.

One particular monolith in the avenue is associated with hunting luck, and before a hunting party goes forth, they go down to the stone and endeavour to kick a pebble on top of it. If they succeed in this, their venture will be successful. At Uilong there is a very remarkable collection of stones.

The unmarried men dance and wrestle inside the large circle on the village genna for the annual festival of the dead.

The fateful i day the maiba pours zu on the stone, "utters many mantras", and lets loose a fowl, in order that there may be no difficulty in i getting the stone into its appointed place. The villagers drag the stone up by sledges like those used by the Manipuris, attaching to them ropes made of the creeper.

Cairns and heaps of stones are found among the Tangkhuls and Quoirengs, who build them in a beehive or conical shape. Some of these beehive cairns are to be seen in the Kaithenmanbi plain close to the cart-road. These stones are all regarded as laipham, places where a lai dwells.

The heaps of stones in the Tangkhul villages and the rings of stones in the Marring villages are holy, so holy that no one dare swear falsely on them. Similar sanctity attaches to a meteor stone in a Kabui village. Good luck in war is associated with the Tangkhul cairns and with single stones such as those kept by the khullakpas at Mao and Maikel. That at Maikel is a mass of conglomerate and is always hidden inside the khullakpa's house.

Dr. Brown mentions the erection by the Kabuis of upright or flat stones as marking the grave, and the only case I have known of the erection of a stone monument took place after the death of the man's father, so that the motive of honouring the dead and of exhibiting piety operates among them to the present day.

God's head is very big, and he has a beard (man was created on the image of God. This God is bearded whereas the Naga people aren't. Where the ancestors of the Nagas bearded Israelites?). His wife once asked him why he killed young people as well as old. He replied, "men cut chillies both unripe and ripe, and after their example I catch both young men and old men".

When a man who has killed an enemy dies, he is given spears and a dao, because he will have to fight again in the path of death. They also give him a spade and an axe to cultivate land in the nether-world.

We can after death reach the holy feet of God in Heaven, if we do not commit any sin and pass our lives honestly in this world; but those who commit theft and do many other sinful actions such as telling lies, cheating others, etc... are all sent to hell.

The ring is worn on the penis, the foreskin being pulled through tightly. The ring is made of bone or bamboo, occasionally of cane ribbon, and is an eighth of an inch to a quarter of an inch wide (is this an evolved form of circumcision?). This "mutilation" is undoubtedly an initiation rite.

Does totemism exist in Manipur in any of its many stages of development or decay? The objects which are ndmungha to the Meithei clans may be provisionally called totems. Among the surrounding cognate clans there are no signs of totemism, but there are some reasons for thinking the Manipuri ' Yek ' is a totemistic division. That there are tabus affecting social units both among the Meitheis and the Nagas is a fact.

Naga Culture, Traditional Religion and Christianity in Nagalim

The word Naga is an exonym. Before the arrival of the British, the term "Naga" had been used in Assam to refer to certain isolated tribes. The British adopted this term for a number of tribes in the surrounding area, based on loose linguistic and cultural associations. Some tribes, such as some of the smaller "Old Kuki" tribes have attempted to get absorbed into the Naga identity to increase their political profile.

The Ethnologue uses the term "Naga" to describe 34 languages in the Kuki-Chin-Naga family. The Kuki of Nagaland have been classified as "Naga" in the past, but today are generally considered a non-Naga tribe.

The Nagas consist of about forty ethnic groups, numbering approximately two & a half million people. Their homeland, known as the Naga Hills during the British colonization, is bordered by India in the southwest, China in the north and Myanmar in the east. Politically Nagas live in a number of colonially segmented regions within India and Myanmar. The Nagas in India alone live in four different states: Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur and Nagaland. In Myanmar they inhabit the provinces of Sagiang and Kachin.

As of 2012, the state of Nagaland officially recognises 17 Naga tribes. In addition, some other Naga tribes occupy territory in the contiguous adjoining states of Manipur, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh, India; and across the border in Burma. Prominent Naga tribes include Angami, Ao, Chakhesang, Chang, Khiamniungan, Konyak, Liangmai, Lotha, Pochury, Rongmei, Zeme...

The Naga speak various distinct Tibeto-Burman languages specifically from the Kuki-Chin-Naga geographic clustering of languages including Lotha, Angami, Pochuri, Ao, Poula (Poumai Naga), Inpui, Rongmei (Ruangmei), Tangkhul, Thangal, Maram, and Zeme. In addition, they have developed Nagamese Creole, which they use between tribes and villages, which each have their own dialect of language. Other languages spoken by the Nagas are English, Hindi.

Naga people speak over 36 different languages and dialects, mostly unintelligible with each other. Naga languages can be grouped into Western, Central and Eastern Naga groups. The Western group includes among others Angami, Chokri, Kheza and Rengma. The Central Naga group includes Ao, Lotha and Sangtam, while Eastern group includes Konyak and Chang.

In addition, there are Naga-Bodo group illustrated by Mikir language, and Kuki group of languages illustrated by Sopvama (also called Mao Naga) and Luppa languages. These mostly belong to the Tibeto-Burman language group of the Sino-Tibetan family of languages.

In 1967, the Nagaland Assembly proclaimed English as the official language of Nagaland and it is the medium for education in Nagaland. Other than English, Nagamese, a creole language form of Indo-Aryan Assamese, is a widely spoken language. Every tribe has its own mother tongue but communicates with other tribes in Nagamese or English.

The "Kaccha Nagas" of Manipur communicate with each other in Meitei, the common language of the people of Manipur. However, English is the predominant spoken and written language in Nagaland.

The Naga had little or no contact with the outside world, including that of greater India, until British colonization of the area in the nineteenth century.

Similarities in their culture distinguish them from the neighbouring occupants of the region, who are of other ethnicities. Almost all these Naga tribes have a similar dress code, eating habits, customs, traditional laws, etc. One distinction was their ritual practice of head hunting.

The British first invaded the Nagas in 1832. After the 1830s, British attempts to annex the region to India were met with sustained and effective guerrilla resistance from Naga groups, particularly the Angami Naga tribe. The British dispatched military expeditions and succeeded in building a military post in 1851 and establishing some bases in the region. The British occupied the Naga Hills until 1947 when the Naga homeland was arbitrarily divided and transferred to India and Burma (Myanmar). The first encounter between Western missionaries and the Nagas took place in January 1839.

Mr. Balfour visited the Naga Hills for three months in 1922 and his presidential address was replete with his concerns for the welfare of the Nagas.

Their main religion is Christianity, although some practice Animism. Naga religion did not have a missionary tendency and did not gain followers by conversion. Instead it was passed on to successive generations through oral narrations, myths, songs, rituals, dances and ceremonies.

Nagas perceived time as being cyclical. The traditional year consisted of a cycle of eleven lunar months that revolved around agricultural activities (in a similar way to that of ancient Israel).

“Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them”. Matt: 5: 17

In the light of the above fact one is prompt to ask why the Nagas accepted the Christian faith without much resistant. Is it because of the similarities in the belief system between the Nagas and Christianity or the commonness in the conception of God the factor for the easily acceptance of an alien religion by the Nagas?

The Nagas' indigenous religion is basically a communal religion. In this religion the force of nature are appeased and spirit-worshiping form an important part of religious rites. The Nagas are deeply religious. The worship of the tribes of Nagas involved two main elements- offerings or sacrifices and geena (taboo).

The Nagas believe in the existence of a Supreme God. The Nagas have some crude and indefinite conceptions of a Great Spirit, and an evil one. The Nagas also believe in spiritism, that there are unseen beings, which can be termed as lesser spirits in order to distinguish from the Supreme Being who influences the lives of men.

The Nagas are not comforted by the spirits but rather filled with fears, by the thought that god’s eyes may be upon them. Disaster waits around every corner and threatens even the most capable and intelligent. For the Nagas to be religious mean to be loyal to true to the traditions of the tribes.